Month: October 2015

How can schools be more equitable?

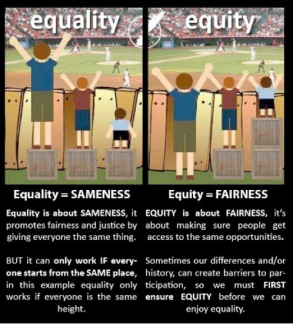

Dictionary.com defines “equitable” as “characterized by equity or fairness; just and right; fair; reasonable.” This is not to be confused with the term “equal,” which is defined as “of the same rank, ability, merit; evenly proportioned or balanced” (Equal, n.d.).

Dana Goldstein (2014) notes that in 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education concluded that not only was de jure segregation (segregation enforced by law) unconstitutional, but that segregation in public schools had a negative effect on children (p.110-111). The desegregation program was one of the first steps taken to achieve equity in education. There was strong resistance at first, from both black and white citizens. Black students and educators were transferred into schools that often did not want them. In fact, two black teachers were transferred into white schools in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, where governor George Wallace “announced he would use police power to remove black teachers from white public schools,” which was enough to scare those teachers away (Goldstein, 2014, p.117). Zora Neale Hurston characterized the issue perfectly in the following statement: “The whole matter revolves around the self-respect of my people. How much satisfaction can I get from a court order for somebody to associate with me who does not wish me near them?” (Goldstein, 2014, p. 112). What a sad yet accurate truth of racial sentiments of the time. According to Goldstein (2014), for the decade following the ruling of Brown v. Board of Education, “desegregation was the law, but not the reality” (p. 113).

It seemed that “separate but equal” facilities were not equal at all. In an effort to create more equal facilities, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) was implemented in 1965 in order to fill in the federal funding gap “for the 19 percent of low-income public school students falling behind in poor, largely black and Hispanic schools” (Goldstein, 2014, p. 114).

In fact, more federal funding would be given to states that provided their low-income students with additional state-level funding. This is quite an incentive, considering that the majority of funds for education come from the state and local level, with very little coming from the federal level, as the graph indicates. The wealth of a given community also seems to affect its funding. According to an article entitled “Public School Funding in Texas,” the Robin Hood system was put into place in 1993. This system involves “the practice of taking property tax revenue from richer districts and redistributing it to poorer districts in an attempt to equalize school funding throughout Texas” (Public school funding in Texas). Due to heavy criticism, the Supreme Court ruled this practice unconstitutional in 2005. In order for schools to be considered more equitable, appropriate resources need to be provided and put into place so that all students receive equal opportunity for success. Minimal federal funding for education continues to be an issue today.

In fact, more federal funding would be given to states that provided their low-income students with additional state-level funding. This is quite an incentive, considering that the majority of funds for education come from the state and local level, with very little coming from the federal level, as the graph indicates. The wealth of a given community also seems to affect its funding. According to an article entitled “Public School Funding in Texas,” the Robin Hood system was put into place in 1993. This system involves “the practice of taking property tax revenue from richer districts and redistributing it to poorer districts in an attempt to equalize school funding throughout Texas” (Public school funding in Texas). Due to heavy criticism, the Supreme Court ruled this practice unconstitutional in 2005. In order for schools to be considered more equitable, appropriate resources need to be provided and put into place so that all students receive equal opportunity for success. Minimal federal funding for education continues to be an issue today.

Today, many teachers adopt prejudices regarding the “culture of poverty,” often thinking that the poorer students in our classes have no hope. One commonly assumed myth is that poor parents are less involved because they do not value education in the same way that wealthier parents do. In “The Myth of the ‘Culture of Poverty,’” Paul Gorski (2008) clarifies that low-income parents are less involved simply because they have “less access to school involvement than their wealthier peers” (p. 33). For example, low-income parents tend to hold multiple jobs, therefore having less access to paid leave, such as is common among their wealthier counterparts. What then develops among teachers is this belief of the “culture of classism” (Gorski, 2008, p. 34). Stereotyping often stems from this idea. This also drives teachers to have “low expectations for low-income students” (Gorski, 2008, p. 34). As teachers, we cannot afford to adopt these views. A child should not be defined by their family situation.

What can we do to change our mindset as we go into the future? Gorski (2008) advises that we should “help students and colleagues unlearn misperceptions about poverty” (p. 35). We need to teach our students to accept others wholeheartedly and encourage community in our classrooms and schools. Do not allow stereotypes in the classroom. We need to view each child equally as having the same potential for success. We need to be advocates for our low-income students especially and ensure that “school involvement [is] accessible to all families” (Gorski, 2008, p. 35). Whether that means meeting with a parent over the weekend in order to ensure that their child succeeds, or sending transportation to their house so they can be involved in a classroom event, we need to go the extra mile to show these students and their families that we believe in them. Our attitudes toward the children in our class is what will make or break the way they see themselves. All it takes is one person to make a difference in a child’s life.

References:

Equal. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/equal?s=t.

Equitable. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/equal?s=t.

Goldstein, D. (2014). The teacher wars: A history of America’s most embattled profession. New York, NY: Random House, LLC.

Gorski, P. (2008). The Myth of the “Culture of Poverty.” Educational Leadership, 65(7), 32-36.

Public school funding in Texas. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.texastribune.org/tribpedia/public-school-funding-in-texas/about/.

Teacher’s rights

There is growing controversy over what rights should be protected for teachers. Here, I examine the experience of Mary McDowell, given in The Teacher Wars, and determine which rights should be protected for teachers.